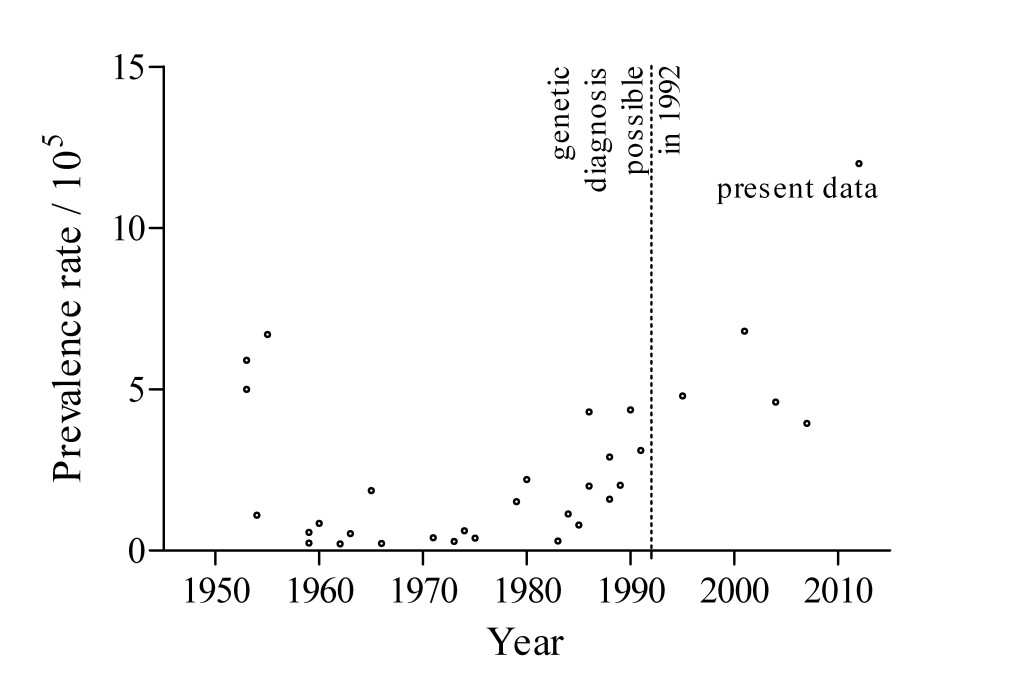

Many researchers have long suspected that the number of individuals with FSHD is significantly greater than has been reported. A new study from the Netherlands bears out this suspicion and finds that the prevalence of FSHD is 12 in 100,000 (or one in 8,333)—more than double the commonly cited figure of five in 100,000.

At the new rate, the worldwide population of people with FSHD stands at nearly 870,000, assuming that FSHD occurs at the same rate across all human groups. This is a big assumption and demands further investigation. That said, the Netherlands for many years has had a robust and well-documented registry with widespread participation, and so there is a good likelihood the study is accurate, at least for the Dutch population.

The new Dutch study employed a method called “capture-recapture,” commonly used to estimate the size of wildlife populations. With this method, one might capture and tag a large number of turtles, let’s say, and then release them back into their pond. One would then capture a second group of turtles from the same pond. A fraction of these newly caught turtles would carry tags, showing that they were part of the first group. From these data, a statistician can calculate the total population of turtles in the pond.

The Dutch team used three large, national registries of neuromuscular disease and genetics to “capture” FSHD patients and then, using patients’ initials and birthdates as the “tags,” were able to determine the degree of overlap among the three registries.

This capture-recapture analysis allowed them to calculate the incidence of FSHD—that is, the number of newly diagnosed cases per year. They found that the mean age at diagnosis among the registered FSHD patients was 42 years, and with an average life expectancy of 39 years from the age of diagnosis, they concluded that the prevalence (number of individuals with FSHD) was 12 in 100,000.

“This study shows that the total number of symptomatic persons with FSHD in the population may well be underestimated, and a considerable number of affected individuals remain undiagnosed,” the study’s authors conclude. “This suggests that FSHD is one of the most prevalent neuromuscular disorders.”

Importantly, the study indicates that a large proportion of individuals with FSHD are not being diagnosed—and therefore are not getting counted. One reason is that many have mild symptoms that go unnoticed by themselves and their doctors. Another is that FSHD patients are told there is nothing that can be done for them. Knowing this, their relatives who exhibit symptoms may not bother to seek a doctor’s diagnosis or care.

Does any of this sound familiar from your own experience with family members?

These are serious challenges for the FSHD community. If the numbers of affected individuals are undercounted, this makes it more difficult to raise the resources and investment needed to combat the disease.

The tens of thousands of mildly affected individuals who are not being counted, and not volunteering for research, are also the same individuals who may hold the keys to aid the more severely affected. They may have genetic or other factors that have protected them—factors that could provide insight for future treatments.

The fates of people with FSHD across the spectrum, from the mildly to the most severely affected, are inextricably bound together. How can we foster a sense of urgency around joining forces to solve this disease? It’s time to start having these conversations. Please consider speaking with your undiagnosed family members and encouraging them to reach out to the FSH Society so they can be counted. Thank you!

Reference: Deenen JC, Arnts H, van der Maarel SM, Padberg GW, Verschuuren JJ, Bakker E, Weinreich SS, Verbeek AL, van Engelen BG. Population-based incidence and prevalence of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy.Neurology. 2014 Sep 16;83(12):1056-9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000797. Epub 2014 Aug 13. View in PubMed.

Leave a Reply