By June Kinoshita (from FSH Watch Fall 2015 issue)

Click on image below to view full size.

In 2013-2014, the FSH Society funded a study led by Doris Leung, MD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute (KKI) in Baltimore, Maryland, which investigated the use of whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) as a method for detecting and characterizing skeletal muscle pathology in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). An imaging method that is sensitive to changing severity in a slowly progressive disorder such as FSHD could not only improve our understanding of the disease and its progression, but also facilitate quicker clinical trials with smaller sample sizes.

FSHD causes slowly progressive muscle weakness that preferentially affects the face, shoulder girdle, and ankle dorsiflexors, and muscle involvement can vary greatly among individuals. The KKI study demonstrated that WBMRI can detect muscle involvement in diverse parts of the body before loss of strength is discernible on physical examination.

MRI studies show that individual muscles in a single person can progress rapidly while the other muscles are spared. This may help to explain why, in many individuals with FSHD, we observe a slow progression of weakness punctuated by a much more rapid loss of strength at some point in their lives. Early on, when a single muscle is affected, the patient may not experience a loss of strength because surrounding healthy muscles can compensate for the loss. But as these surrounding muscles are affected, they become less able to compensate, and we observe a gradual loss of strength. At some point, when a critical remaining muscle succumbs, we observe a more dramatic loss of strength.

The KKI study used “T1-weighted” imaging to identify the degree of muscle replacement by fat. In addition, using a technique called STIR (short T1 inversion recovery), the investigators could use MRI to detect muscles with edema (fluid infiltration), which they think represents an active inflammatory phase that precedes the replacement of muscle by fat.

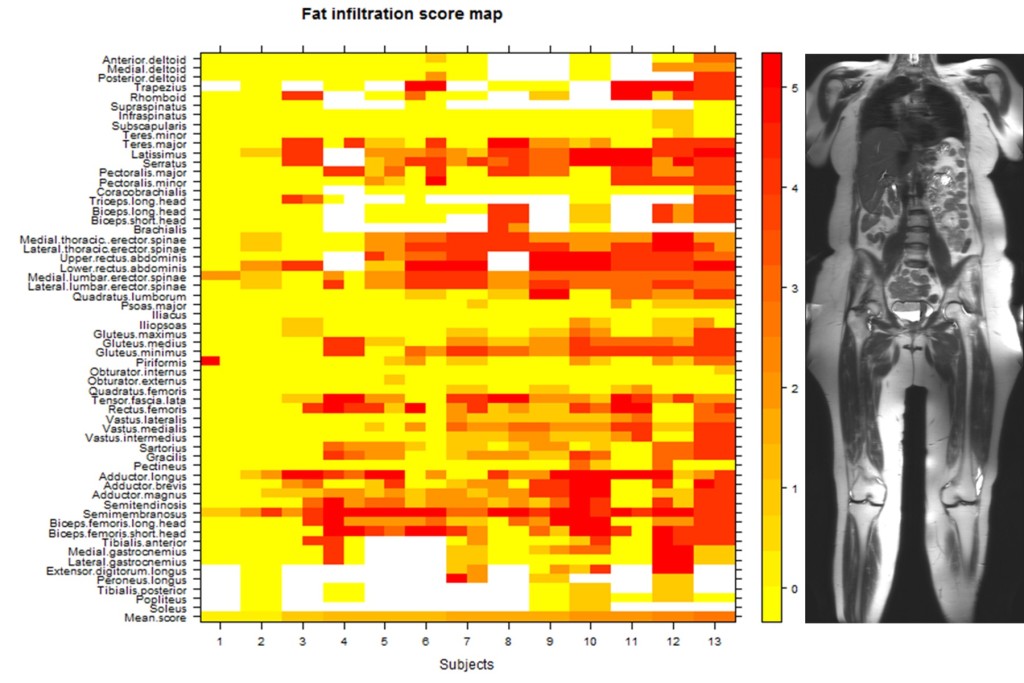

Thirteen individuals (eight men, five women) were enrolled in the study. They ranged in age from 20 to 72, with a mean age of 48 years. All of these volunteers completed the study in its entirety, and no complications were reported. For each subject, 92-118 muscles were visualized and given scores for fat replacement and edema-like abnormalities.

These volunteers varied considerably in their disease severity. The percentage of muscles that were affected in individual subjects ranged from 3 percent to 75 percent. The most frequently and severely involved muscle overall was the semimembranosus (one of the hamstring muscles in the back of the thigh). Muscles of the trunk (including the paraspinal muscles and muscles of the abdominal wall) were also among the muscles involved most frequently.

Conversely, several muscles were frequently spared in the study population. In all 13 volunteers, the following muscles were unaffected: the iliacus, obturator externus, and obturator internus (in the hip and pelvis); subscapularis (rotates the head of the humerus); and infraspinatus and teres minor (parts of the rotator cuff).

Although the investigators lacked historical imaging data on the volunteers, they reasoned that the muscles that are affected most frequently across the study population are those that must have been affected earlier in the disease process. The frequent involvement of the hamstring muscles in nearly all of the volunteers, for instance, suggests that the hamstrings are among the earliest muscles affected in FSHD. Yet knee flexion weakness, which one would expect to see as a result of hamstring weakness, is rarely an early clinical complaint. This is likely due to compensation by the remaining muscles in that muscle group.

Why is this important? It suggests that imaging of the hamstring muscles is an early indicator of disease progression, something that might not have been recognized based purely on clinical strength measurements.

Only a minority of muscles (three to 14 muscles per subject) were hyperintense (presumably because of edema) on STIR imaging. Over the entire study population, only 79 of 1,330 muscles fell into this classification. Although STIR hyperintensity was associated with all levels of fat infiltration, it was rarely seen in muscles with the highest fat infiltration. This observation supports a hypothesis that STIR hyperintensity reflects an inflammatory process associated with early stages of muscle degeneration.

Another part of this study that Leung says she finds interesting is the inclusion of asymptomatic individuals. “Several participants in this study did not have any muscle weakness but were found to have the mutation that causes FSHD through genetic testing that was done after a family member was diagnosed,” she said. “In some of these individuals, we were able to find affected muscles on MRI, what we call subclinical (non-symptomatic) disease. Studying this population could give us valuable insight into factors that modify the severity of FSHD.”

The ability to detect these subclinical changes in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals is a major advance toward clinical trial preparedness in FSHD.

“Although this study population has been extremely informative, it is still a very small study sample,” Leung cautions. “There is tremendous variability in the FSHD population, and a small study can’t hope to capture that variability. A crucial next step in developing MRI as a tool for studying FSHD will be to scan a larger number of individuals over time. I also think that it will be very informative to target the earliest stages of disease by imaging newly symptomatic individuals in the pediatric and adolescent populations.

“In the future, studies in larger numbers of patients will be crucial for developing any imaging biomarker that we may propose to use in clinical trials. In our study we excluded non-ambulatory individuals and individuals who had scapular fixation surgery. Both groups represent more severe manifestations of FSHD and should be included in future studies.”

Leung notes that this research wouldn’t be possible without ongoing collaboration among radiologists, biomedical engineers, radiographic technicians, and clinicians in our own institution. “Maximizing the potential of MRI as a research tool will require studying patient populations at multiple locations, so we will need to collaborate with investigators at other institutions as well,” she says.

Reference

Leung DG, Carrino JA, Wagner KR, Jacobs MA. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2015 Oct;52(4):512-20. doi: 10.1002/mus.24569. Epub 2015 Mar 31. PubMed link.

Editor’s note: Jim Fox wrote a great first-person account of participating in this research study. See the Spring 2014 issue of FSH Watch. The FSH Society supported this research through a grant award to the project called “Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy Biomarkers in FSHD.” Investigators: Doris G. Leung, MD, and Kathryn R. Wagner, MD PhD, Hugo W. Moser Research Institute at Kennedy Krieger, Baltimore, Maryland. From August 2011: $100,550 over two years.

Leave a Reply