by Haviva Ner-David, Kibbutz Hannaton, Israel

It was a chance meeting in the valley that divides my Galilean kibbutz Hannaton from the Bedouin village of Bir al Maksur that planted the seed for the storyline of my debut novel, Hope Valley. I was out walking my dog when I saw Hussein, a shepherd who frequents the valley, out with his sheep. But this time, his wife was with him. She was foraging.

“Sabakh el kher,” I said.

“Sabakh el nur,” she answered.

Despite my only elementary Arabic and her practically non-existent Hebrew and English, we found a way to communicate, especially with the help of Hussein’s translation. When she asked me how old I was, and I told her, she started to cry. Her daughter, who had recently died from cancer, was my age.

When she told me more about her daughter, I said I wished I had met her. And that was the truth. I began to think how, if we had met, we might have connected over being ill, despite the cultural differences and history of conflict between our two peoples. I was diagnosed with FSHD at age 16, the first in my family that we know of with FSHD (although no one else was tested, except my children, so we’ll never know if I am a spontaneous mutation or not).

As we know, FSHD is not necessarily fatal, but as the disease progresses, it can be, if it spreads to the respiratory system. I am already experiencing the effects of a weak diaphragm.

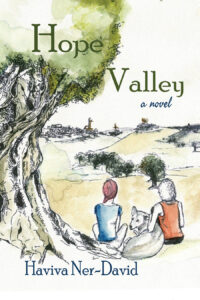

And thus was planted the seed of the idea for my novel, Hope Valley, which is about the unexpected friendship between Tikvah, a Jewish-Israeli woman with multiple sclerosis, and Rabia (or Ruby), a Palestinian-Israeli woman, who has lung cancer. The two women meet one day in the Galilean valley that divides Tikvah’s moshav (farming community) from Ruby’s village. While at first there is suspicion and resentment between them, they slowly become friends.

Tikvah is not me, but there are aspects of her with which I identify and wanted to explore in the novel.

Multiple sclerosis, like FSHD, is a degenerative neuromuscular disease, so, like me, Tikvah deals more than a healthy person does with the uncertainty of tomorrow. She feels viscerally that her days are numbered. It is for this reason that she feels an urgency to find her life’s purpose and live the days she is given in spiritual alignment.

I wanted to explore the idea of two women connecting across hostile national lines by their shared experience of illness. I wanted to have both women express the nuances of living in a disabled or diseased body. For example, this quote about Tikvah: “That was the most exhausting thing about her illness—trying to convince everyone she was okay so as not to alarm them, and then trying to hide her resentment at their lack of alarm.”

I purposely chose not to have Tikvah’s disease be FSHD, because I wanted to retain some distance from the character. Hope Valley is a novel, not memoir. I have written two memoirs (and have a third on the way) in which I write explicitly about living with FSHD.

But writing fiction is different from memoir. One must identify and sympathize to the extent of being able to write from the character’s point of view, but one must not overly identify, so as to leave room for the characters to take on a life of their own.

I am not Palestinian, and I do not live with MS. But I do live with a somewhat similar disease, and I do have friends who are Palestinians and have shared with me their stories. This feels especially appropriate considering the main theme of this novel, which is about sympathizing with the other.

In writing this novel, I was engaging in the same act that brings the two main characters together. I stepped into the shoes of both women, just as they were stepping into each other’s shoes. If Hope Valley can help readers better understand someone living with a degenerative and debilitating illness, as well as both narratives in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, I will have accomplished at least two of my goals in writing this novel.

Hope Valley is available on Kindle and in paperback on Amazon.

Excerpt from Hope Valley, by Haviva Ner-David

Tikvah put a hand on her friend’s arm and asked her the question to which she did not want to know the answer. “What’s going on, Ruby? Now it’s your turn to tell me what’s wrong,” she said, remembering that day in the forest when Ruby had encouraged her to share.

That tear stubbornly fought its way down Ruby’s cheek. Then another. “It’s spread to my brain. The cancer. Khalas! My incarnation in this body is coming to an end, and I want to be as present as possible for the time I have left. More treatments may give me a bit more time, but with too much of a price. I’ve accomplished my work in this life. Thanks, in part, to you. I thought if anyone would understand, you would.”

Tikvah went cold. She trembled.

No, she did not understand. She knew Ruby was ill, just as she knew she was; but knowing when the end is coming—seeing it before you, as you stand on the edge of a cliff, the wind pushing you from behind as you look down at the vast ocean beneath you—was another thing entirely.

Leave a Reply