An aspect that is often overlooked during drug development is a cost-benefit analysis of a therapeutic treatment. Insurance companies often determine the level of coverage they are willing to provide for a new treatment based on the cost of the drug relative to the perceived cost to society. Unfortunately, insurance actuaries may model the socioeconomic burden of an indication using inaccurate figures and grossly underestimate the impact a disease may have on an individual, a family or a community.

An aspect that is often overlooked during drug development is a cost-benefit analysis of a therapeutic treatment. Insurance companies often determine the level of coverage they are willing to provide for a new treatment based on the cost of the drug relative to the perceived cost to society. Unfortunately, insurance actuaries may model the socioeconomic burden of an indication using inaccurate figures and grossly underestimate the impact a disease may have on an individual, a family or a community.

Many of these models are typically based on the insurance claims data that are generated by averaging costs associated with medical visits, types of procedures given and frequency of hospitalization over a lifetime. However, this type of approach fails to include many of the other costs FSHD patients incur during their journey. These “hidden costs” include all out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. genetic testing, home modifications, mobility devices), any loss of income due to loss of employment or forced early retirement, or any of the time provided by family care-givers.

The true costs over a lifetime are undoubtedly significant, but there has been very little research done to date on the broad socioeconomic impact of FSHD. Yet it’s imperative to do so, especially as we get closer treatments. Government agencies and private insurance alike will be weighing the costs and benefits of providing treatment and they may not account for these hidden costs.

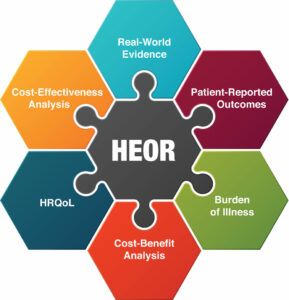

Feeling the urgency to define the value proposition of future treatments, the FSHD Society is undertaking its own health economics outcomes research (HEOR) to get answers to these questions. In the coming year, we will be analyzing several large health datasets covering much of the U.S. population. Our goal is to use real-world data to understand the diagnostic journey, how FSHD patient utilize healthcare and how much it costs, if there are disparities in the quality of care patients are receiving, and so much more. We are also planning a survey-based study to understand the unreimbursed and hidden costs of living with FSHD.

We’ll be communicating with our U.S. patients and families often in the coming year about our progress and to invite everyone to participate in the surveys. And we are encouraging patient advocates in the World FSHD Alliance to undertake HEOR projects in their countries. It is almost unprecedented for a rare disease patient advocacy organization like the FSHD Society to tackle an HEOR project. But for us, it is just one more extraordinary measure we are taking because this is how we help ensure that future treatments can reach every patient.

Extraordinary indeed! Looking forward to the survey. The emotional toll not only on the patient but on the family and the psychological costs as well as costs exacerbating complications and length of recuperation from other illnesses needs to be quantified too.

This study will be fascinating to read. So many aspects of disability are ruinously expensive, yet insurers are willfully ignorant of anything except direct costs to themselves. This leaves a huge gap that the disabled person is expected to cover themselves.

Need a wheelchair-accessible car? That’ll be $75k please, for a run-of-the-mill minivan; and don’t even think about looking for the nothing-down 0% deals that the rest of the car industry takes for granted. They barely exist. Don’t bother trying to lease, either, since leasing-company calculators don’t know what to make of anything but the base cost of the vehicle, so the conversion is priced at full value. This makes leasing a low-spec WAV Dodge about the same monthly cost as a Porsche.

Need a toilet seat that lifts? $2k please, for a cheap plastic product with an underpowered motor.

A wetroom conversion? $25k to you, sir, but don’t ask for any frills.

An indoor/outdoor powerchair that maximizes your remaining mobility and helps relieves chronic pain? Let’s start at $20k, shall we, and if you want positioning, I hope you’ve got at least twice that to blow. All for technology that hasn’t fundamentally changed in 30 years. And don’t ask for help from SS or your insurer with this extravagance, because they don’t think you should be allowed out of your home, anyway.

Every time, the excuse given is that the market is “too small” to benefit from large-scale manufacturing efficiencies, so prices are inevitably high. Yet the products produced are often little different from similar products aimed at the able-bodied market, except for the 500% markup.

I’ve long suspected the DME and similar markets are one enormous grift, fleecing a captive audience with the assistance of clueless regulators and grasping insurers. It’ll be interesting to see if this study dips its toe into these murky waters. I hope so, since a full understanding of the cost of disability needs to explain why the disabled are so grossly underserved and overcharged.