Preliminary findings from our survey to understand the economic impact of FSHD

by June Kinoshita, FSHD Society

As a growing number of drugs enter clinical trials for FSHD, a question we hear is, How much will these treatments cost? Unfortunately, we don’t have a crystal ball. At best, we can say that the price will need to generate enough revenue to satisfy the investors who finance these drug development programs. They are counting on health insurance companies to cover much of the cost.

What we can do is advocate for fair pricing. This means the benefit of new medicines should be greater than their cost. Ideally, this math ought to consider not only the cost to the healthcare system, but also other real, substantial costs borne by individuals and society.

The socioeconomic burden of FSHD in the US is not well understood, so last year the FSHD Society designed the True Cost of FSHD survey. We asked the community to tell us what it costs to live with FSHD—for medical care, equipment, adaptations to homes and vehicles, time lost from work, unpaid caregiving by family members, added costs of travel, and anything else that they would not have had to pay for if they didn’t have FSHD.

A remarkable 312 households representing 354 individuals with FSHD responded. We know it took a huge effort to answer our many questions, and we are deeply grateful!

How we categorize costs

We have been busy analyzing the results. It’s not simple, but we are making progress. At the International Research Congress in Milan, we presented some preliminary findings. We still have a lot of thinking and analysis to do, but we want to share some of our findings to date.

We have been busy analyzing the results. It’s not simple, but we are making progress. At the International Research Congress in Milan, we presented some preliminary findings. We still have a lot of thinking and analysis to do, but we want to share some of our findings to date.

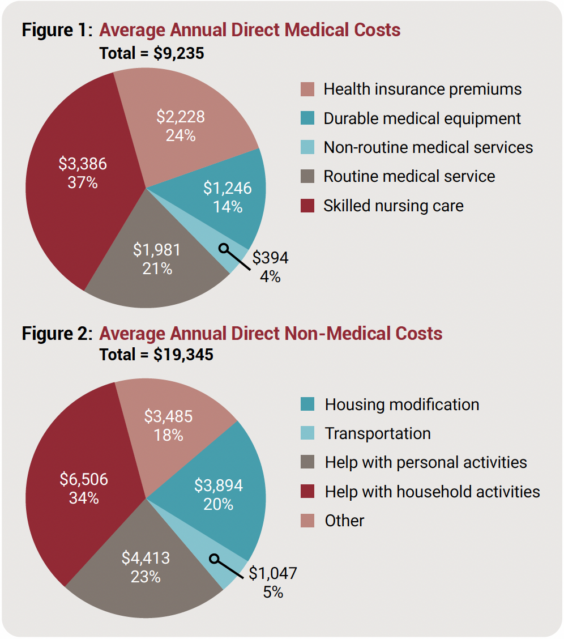

We put costs into three buckets: Direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, and indirect costs. Direct medical costs include all medical products and procedures that patients paid for out of pocket, including doctor and nurse visits, prescribed equipment, medications, and other healthcare services.

Direct non-medical costs include other expenses that are the result of having FSHD. These include the cost of making adjustments to homes, workplaces, and vehicles, and the cost of personal aides and household help, including both paid and unpaid help provided by family care partners.

Indirect costs are harder to tabulate and include “opportunity costs” of lost or altered career paths, early retirement, denial of long-term disability and life insurance, costs of creating families through adoption or reproductive technologies, and so on. We are still working on this analysis, so it is not included in this story.

The pie charts we show here are the average yearly costs reported for direct medical and non-medical costs, which total $28,580 per year. This is an average based on figures reported by everyone who responded to the survey. Many people reported lower yearly costs, and some reported higher costs.

Representing everyone remains a challenge

FSHD varies quite widely in how it impacts individuals. Symptoms and disability get worse over time, so people who have lived with FSHD for many years may have higher costs compared to someone who is recently diagnosed. On the other hand, a newly diagnosed person may show a spike in costs because of all the tests and procedures that were part of the diagnostic work-up.

Another factor we need to consider is that the people who responded to our survey might not be typical of the entire FSHD population. The survey-takers skew older, with 76% over the age of 40, whereas in the overall US population, less than 50% are over 40. Our survey respondents are also more affluent, with 68.9% reporting incomes above $80,000. In addition, 91% of survey respondents are white, whereas whites account for 75.5% of the US population.

We are concerned that our data do not include the costs for minorities, younger, and less affluent individuals. It is likely that we are missing people who don’t have access to good FSHD care. The challenge for all of us is to include everyone.

Leave a Reply