Taking back control of my destiny through research

BY HELOISE HOFFMANN, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

For the past year, I have been working alongside a team of fellow undergraduates at Stanford University to research a therapeutic approach for FSHD. Directing this project has taught me unique lessons in hope, resilience, collaboration, and the goodness of people.

I was diagnosed with FSHD at age 13, after three long years of prodding and poking and yearning for an answer to my symptoms – a path well trodden in the FSHD community. The initial years after my diagnosis left me feeling diminished, shattered, and isolated. But getting involved in advocacy, and now research, has been a life-changing way of taking back control of the disease that once controlled me.

My latest journey started with an impulsive decision to apply for Stanford iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine), a global synthetic biology competition enabling undergraduates to pursue student-driven research at the cutting edges of bioengineering.

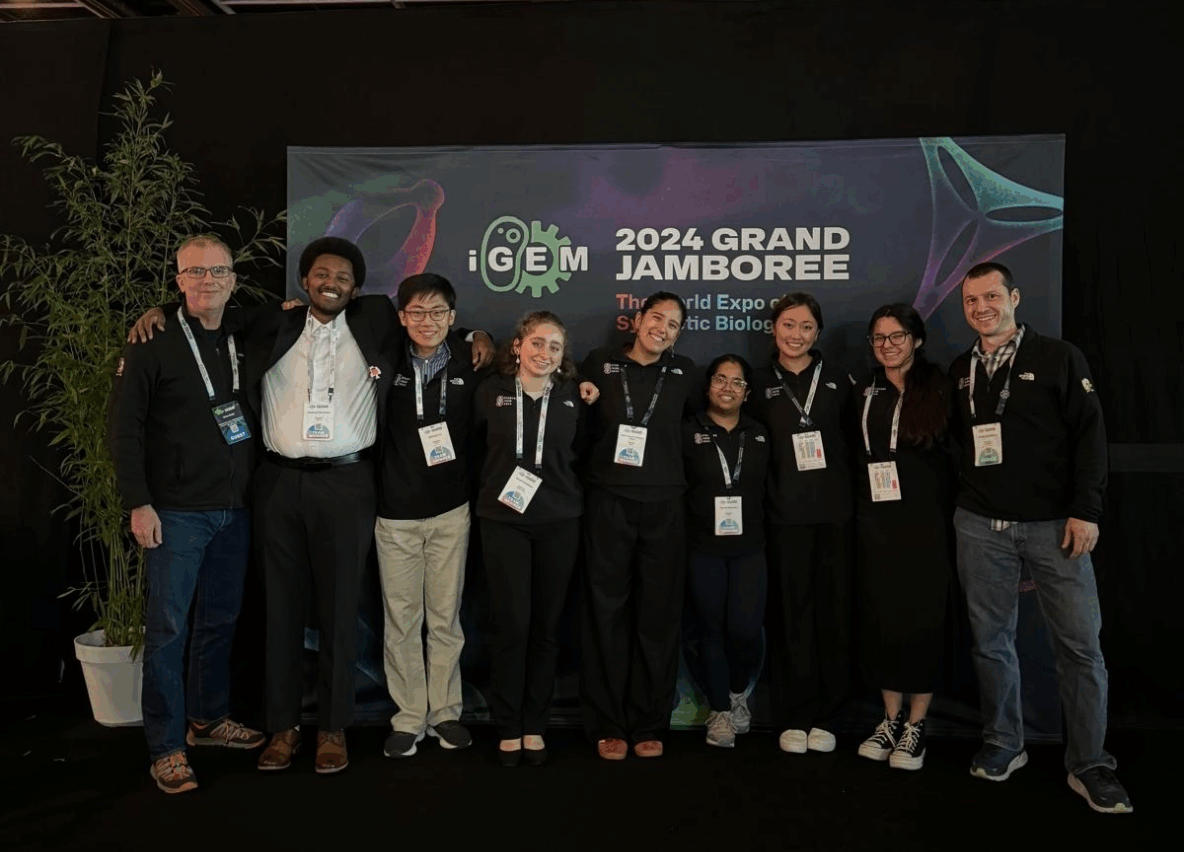

My teammates – Alice Finkelstein, Michael Liu, Mafer Velasquez, Vanessa Chiprez, Katherine Xu, Amanuel Geremew, and Ayushi Mohanty – jumped on board and helped me transform what started as a mere idea into an adventure.

FSHD is caused by faulty expression of a gene called DUX4, which activates a cascade of other genes that is toxic to muscles. Our scientific approach centers around harnessing the inherent DNA-binding properties of one part of the DUX4 protein and repurposing it to silence, rather than activate, its targets.

Excitingly, we found promising results through our early experiments. My team presented them at the annual iGEM conference in Paris in November, raising awareness about FSHD on the global stage. Our team competed in a therapeutic research program through which we secured $50,000 to fund the next steps of our project.

Power of the patient voice

We are now gearing up for new experiments by which we hope to demonstrate that our therapy might work in the clinic.

The past year has been exhausting and frustrating at times, as we worked long hours, encountered problems with our cells, and struggled to get the right DNA sequences. But I have never felt so exhilarated, empowered, and galvanized than when I was in the lab. Looking through a microscope lens at my glowing cells, I thought, “Wow, this could really work!”

As my teammate Alice said, “Analyzing the results of one of our first transfections [inserting new DNA into cells], where we first discovered promising preliminary results from our approach, was magical. The months of effort we had put into planning our project and performing the series of experiments leading up to that moment – from the background research, to cloning and assembling our DNA constructs, to designing the transfection conditions – suddenly paid off, and in that instant, the potential for our idea to be a novel therapeutic approach for FSHD turned real.”

Above the exciting research, one of our main priorities was elevating patient voices. As a patient, I know how frustrating it can be to feel left out from the research and the exciting advances being made in the field.

Thanks to exceptional efforts by my teammates and collaboration with the whole FSHD community, we interviewed more than 20 clinicians, researchers, and other professionals, and, more importantly, consulted with dozens of patients to ensure their voices are heard in the research process.

“Handling the patient interviews was the experience I value the most out of everything I did during the summer,” said Mafer. “Listening to stories, understanding the multifaceted nature of FSHD, and knowing the special cases of each of our conversations shed light onto multiple aspects of our project. But more than that, it gave us the determination to keep working to make this project an accessible reality.”

Community is our superpower

Working as a team to unpack FSHD, which is commonly characterized by scientists as one of the most complex genetic disease mechanisms, has been beyond inspiring and empowering.

“It was incredible to see how our research could help uncover new possibilities for treating FSHD and give hope to those living with this condition,” enthused Katherine. “Working alongside such passionate teammates has shown me how powerful collaboration and innovation can be in tackling real-world challenges. Not only was it an exciting intellectual challenge to work on computational models in a field in which I was not an expert, but the connections built through this experience were what inspired me the most.”

Going into 2025, I am more excited and hopeful than ever about what’s coming our way. We are at a pivotal moment in FSHD history; we know the gene causing FSHD and how to stop it, and there is more interest than ever from researchers to tackle it.

Above all, we have a secret superpower: A community of patients, their families, and their cheerleaders, with a greater sense of grit, resilience, and adaptability than I’ve encountered anywhere else.

So let’s roll up our sleeves, put our heads together, and use our superpower to once and for all show FSHD who’s in control!

In addition to my wonderful teammates, I would love to thank our iGEM mentors at Stanford, Helen Blau, Michael Kyba, June Kinoshita, and all the others involved in shaping our project. Without their mentorship and encouragement, we could not have had the same impact!

Leave a Reply